Harlem’s drag balls started at least as early as 1869, with records of them taking place at Hamilton Lodge (aka Rockland Palace). Initially these balls were a secret known solely within the gay, predominantly Black, communities who welcomed the safe places to congregate and enjoy themselves. But even as the drag balls grew more popular over the decades, and became slightly less of a well-kept secret, they continued to be considered immoral by wider society. Running a drag ball or congregating at one was illegal and, once the Committee of Fourteen (a self-termed ‘moral reform’ group) became aware of them in the early 1900s, they set about investigating them with zeal.

In 1916, the Committee of Fourteen released a report about the drag balls decrying them as places of perversion and sin, then continued to release more than 100 more reports with increasing demand that these drag balls be stopped for good. Despite police raids, efforts to turn public opinion against the balls, and church leaders and government officials alike denouncing those who attended the balls, they only grew more popular through the 20s and 30s.

By this point, the wider public knew about the balls, and while they were still often referred to in unfavourable terms (frequently called “Faggot’s Balls”) for example, there is probably a wider context for why so many people — particularly the white middle-class people the Committee hoped to galvanise against the drag balls — did not react in the overt way the Committee hoped and demand the closure of the balls.

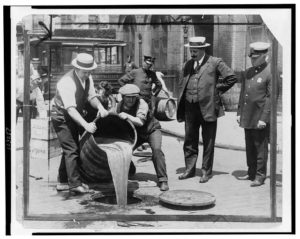

Prohibition.

Prohibition came into effect in the United States in 1920 and lasted until 1933. Alcohol sales in many of the places where white, cis, straight people went to drink either became limited or dried up completely, depending on how quickly the owner was able to get hold of bootleggers and other sources of illegal stock.

And bootlegging quickly became an occupation that was open to people of all races, genders, and sexual orientations. Strangely, the people of the time managed to put their bigotries aside when it came to getting hold of alcohol. Speakeasies cropped up all over the place; plenty of them inside Black neighbourhoods or in places that catered predominantly to the gay community.

The mafia also got involved in bootlegging and speakeasies, seeing an opportunity to make a lot of money. The Mafia controlled Manhattan’s West Side which included the Village — an important hub for gay communities at the time — and most weren’t particularly concerned who was drinking in the bars they ran or took over, so long as they got their money.

Police were paid to look the other way and pretend they hadn’t seen or heard anything, and with the thrill of the underground bars came a greater desire for entertainment. Jazz, drag balls, and drag artists all became commonplace and celebrated in places frequented by a more diverse clientele than would ever have attended pre-prohibition. This was colloquially termed the “Pansy Craze”.

With the general social climate of law-breaking in pursuit of alcohol, many people became less concerned for a short-time about the comings and goings of people who were LGBTQA+. It became easier to either slip beneath notice and carry on with your business undisturbed, or to be celebrated as part of the entertainment which came with attending a speakeasy.

This inclusive and accepting environment was not, however, based on true, mutual respect. It was wrapped up in being a means to an end for people to get hold of alcohol, and so — to little surprise — when prohibition was repealed in 1933, people left the speakeasies and nightlife of the Black and gay communities behind, and returned to the new bars opening in their own neighbourhood. To make matters worse, many new state liquor licenses after prohibition returned with the clause that alcohol could only be served in places that were “orderly” (other, similar language such as that decrying degeneracy or immorality, etc. were also used).

LGBTQA+ bars and nightclubs were not deemed orderly and bigotry towards the gay community began to increase again. Black and Asian run speakeasies or bars suffered at the hands of racism, where imaginary or minor infractions were used as fuel for police to raid the bars. Many of the same bars which the police themselves would have drank in before 1933.

Sources used for notes:

The Oft-Overlooked ‘Drag Balls’ of Harlem

Reflections on Black History – Thomas C. Fleming

Prohibition: An Interactive History

How NYC’s gay bars thrived because of the mob

Queens and queers: The rise of drag ball culture in the 1920s

The Hamilton Lodge Ball

During Prohibition, Harlem Night Clubs Kept the Party Going

How Gay Culture Blossomed during the Roaring Twenties

In the Early 20th Century, America was Awash in Incredible Queer Nightlife

Be First to Comment